Follow the school, and the predators will eventually emerge. Courtesy Jeff Little

BY JEFF LITTLE

It had been a good day of fishing, and there was still time on the clock. But I was cold. Hours had passed since my toes had sensation. Pumping my ankles in an attempt to push in some warm blood, I could see my boots moving, but couldn’t feel the joint rotating. “Hey man, let’s call it!” I called over to Dave. He agreed and we started the long paddle back to the ramp.

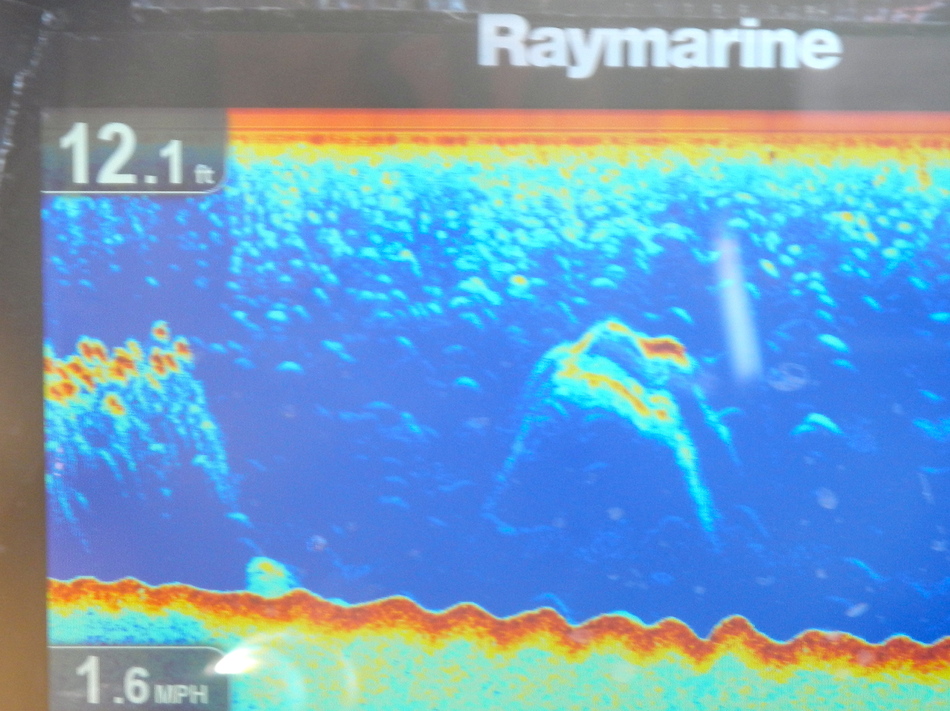

A minute later while glancing down at the depth finder, I dropped the paddle and picked up a rod. Dave glided alongside in time to see me unholster the 1.5-ounce lead head and soft plastic lure from the hook keeper. He smiled and laughed.

“I just can’t help myself!” I said, trying to explain my change of heart. The marks on the screen just couldn’t be ignored: vivid and dynamic, a pod of baitfish 10 feet tall, sprinkled on the perimeter with darker predator fish marks. Opening the bail on my spinning rod, I let the heavy lure quickly pull 15-pound braided line coils down with it until an abrupt stop 48 feet later.

The choice for spinning gear over a baitcaster was based on needing to let a lure free-fall as soon as the depth finder shows you over the meat of the baitfish school. Any resistance in the lure falling through a tidal current is like having an arrow miss its target in a strong cross-wind. The fall has to be immediate and fast. It needs to land in the school of baitfish, not 10 feet to either side.

I flipped the bail closed, gave it a rip and felt the jighead bash into something about two feet into the upswing. I assumed it was a collision with one of the many shad below making a cloud of red on the monitor. Ichthyologists believe that a injured baitfish send out chemo receptors into the water, letting the rest of the school know of the attack, putting the entire school in a state of heightened alertness. Predator fish likely also “smell” the fear when a baitfish is injured.

So lowering the bait down as slow as I could, almost hovering in place, I felt the distinct movement of the bait being suctioned backwards in current. Then came the crunch of a striped bass closing its mouth. That sensation—that moment of feeling the hit, seconds before arms swing the rod tip up to bury the point—that’s the exactly thing we seek, again and again.

The author, with his cold-weather catch of the day.

I looked at my rod’s deep bend and knew that it was not one of the many 18 to 21 inchers we pulled to the surface earlier in the day. It was bigger. I brought the fish half of the 50-foot distance to the surface when it decided to do more than shake its head back and forth. The rod tip and half the length of rod was pulled down into the water, the bright yellow line ripped from the spool in two long surges.

At the end of its downward run to 48 feet deep, I noticed what had transpired on the depth finder. Five distinct marks had followed my hooked fish up, then chased it back down. I looked over at Dave and said, “Quick, get your lure down there! Cast right on top of my fish!” When an entire pod of fish is excited, they are easy to catch. It didn’t work for Dave in that instance, but it’s always worth a try.

The fish made one more good run once near the surface. This time I could see the followers: four distinct, long silvery-purple and olive-striped torpedos. They were similarly large fish. Finally exhausted, the striped bass gave one more heavy head shake, slapping the surface of the water. Heaving the almost 30-inch-long fish into my kayak, I took notice. I could feel my toes again! Adrenaline somehow must increase blood flow to the extremities.

THE PROCESS

Dave took some photos and then we started our search for pods of baitfish again. The process started with me running my Torqeedo trolling motor at a low speed on a path parallel with the channel edge, hands ready on the spinning rod to flip the bail as soon as the right marks appeared on the screen. Dave would be a quarter-cast to either side of me, easily paddling the same speed, with the tidal current. When either of us would see a school of baitfish on the depth finder, we would call it out, “I’m on ’em!” and then converge on the pod.

If you could feel the jig bumping fish on the upswing, you hit the target. If not, you needed to paddle farther down the channel to place yourself directly over the school. The best way to make sure you were directly over the school was by studying the intensity of the cloud of marks on the depth-finder screen before deciding when to drop the jig. Easing over the edge of the school, a faint green would start to shade in, then a transition to a yellow. When I saw shades of orange change over to a well-defined red, center mass of the school, I knew it was time to free spool.

Most of the times I felt a hit, I had presented to the center mass of the baitfish school then drifted, becoming misaligned with it. To me, this meant that my bait represented one of the baitfish that separated from the school, providing an easy, singled-out target. Whatever the case, the best likelihood of catching followed the sequence of: one, finding the school; two, dropping your lure fast; three, jigging up through the school; and four, letting the bait hover within a foot or so of bottom. In warmer temperatures, the continual jigging does the trick, but in 35-degree water, most of the takes were with the bait simply hovering above bottom.

Five days later, I returned to the same area, failed to find those schools of baitfish, and failed to land any fish. Whereas on the day with Dave, we found at least a dozen different large schools of baitfish, the second day I found only one. Instead of hunting schools, I hunted individual marks. The tactic yielded two bites, neither of which I landed. The disparity in those two days of just reinforced the idea that to find a reliable bite, you have to follow the food.

Fishing Articles : Bennet Springs State Park

Jetty fishing 101 - Tillamook Barview Jetty

Copyright © www.mycheapnfljerseys.com Outdoor sports All Rights Reserved