Chilo Martinez lives in the little seaside village of Parismina on Costa Caribbean coast. He always has. Martinez is a fishing guide at Rio Parismina Lodge, which specializes in tarpon and exotic freshwater species and is right across the river from where he grew up. He fishes privately, too, though not for sport. He also has a passion for hunting the surrounding rain forest for wild pigs, rogue crocodiles or anything else that threatens the little farms set back from the lagoons and rivers of this country.

On the water Chilo is the guy you'd want in charge if a tarpon jumped into your boat. You'd also want him on your side in a San Jose bar fight. I watched recently as the man, well into his 40s, took the end of a derelict commercial net from the hands of two sporting clients struggling to bring the mesh into his boat. Without speaking, Chilo pinwheeled in yards of dead-weight net hand over hand as if it were kite string. His motions were swift and sure, almost mechanical. As he stared into the water, it may be that he was reliving the nightmare of his past.

FERTILE WATERS

Central American rivers, like rivers in the United States, flush out debris from far inland. Curious items drift by en route to the sea--whole trees, banana bunches, the occasional dead cow. The river outlets where this motley flotsam spews into the ocean contain a rich stew of nutrients that attract small and large fish, including hammerhead and bull sharks. In looks alone, their eyes set on T-stalks protruding from their heads, hammerhead sharks are grotesque, scary creatures. But a unique trait makes bull sharks potentially more dangerous: These saltwater creatures can survive in fresh water. Stocky and broad-snouted, with high-sailing dorsals, bulls freely enter freshwater rivers. In Central America they have been known to swim more than 100 miles up the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua, where they've killed unsuspecting bathers wading near shore. If you hook a tarpon at the mouth of one of these rivers, there's a good chance you'll lose it to a shark.

The river outlets on Costa Rica's Caribbean coast are marked by high surf and treacherous cross currents. During the 1970s, camps here fished their clients from small aluminum skiffs, and on days when the surf was down, guides ran out to fish tarpon in the Caribbean Sea. The tarpon schools seemed endless at times, and everyone wanted to fish there. It wasn't until Rio Parismina Lodge started running 21-foot center-console boats, however, that fishermen could count on consistently reaching the ocean, and it's still a white-knuckle ride. Some days it can't be done at all. Before the coming of the big boats, skiff fishermen at other camps pandered to their guides' machismo and tempted them to run the outlets when conditions were bad with promises of big tips. Over the years fishermen and their guides were lost when the small boats sank in surf and undertow. But not all the fishermen whose skiffs swamped in the unpredictable waters here died by drowning.

A RISKY RUN

On the village side of the Parismina River outlet the gray sand beach is cluttered with driftwood--huge logs, whole trees with interlocking branches bleached like bones from the sun. Buzzards with their obscene naked heads hop awkwardly on the sand in search of decaying fish or animal matter. Higher up on the headland a makeshift driftwood fence corrals a small herd of horses; it was erected in hopes of keeping them safe from jaguars patrolling the rain forest perimeter. Chilo Martinez was 17 when his father made the decision to run the outlet in a dugout canoe with two male friends.

When the surf was down, villagers often used their long, locally hewn dugouts to run the river mouth and travel the coast, and in this case the senior Martinez's decision was made for good reason. His wife, Chilo's mother, was ill in the clinic of Puerto Limon, a coastal town south of Parismina. It's possible to reach Limon through connecting waterways upriver, but the trip is long and Martinez had received word to come at once. His wife was in serious condition.

The sky was gray and the wind and surf were building when the elder Martinez and his two friends pushed their boat into the river. They made it halfway out through the breakers before the dugout swamped. The canoe filled with water, losing its resilient flexibility. Caught between the cross-running waves and the incoming surf, it broke in two. Chilo's father swam for shore, believing his friends were with him. Clawing through undertow and stumbling to his feet, he turned to see the other men still clinging to the pieces of the dugout. Some of the villagers had been watching and now ran for help, whether for rope or another dugout is not known. The senior Martinez did not wait. He turned back to the water and began swimming to his friends. The bull sharks hit him inside the big surf.

The first shark to attack stopped, dorsal high, closing down with that horrible side-to-side, tearing shudder. The others bore in instantly, crazing the surface, and the surrounding water turned brown with blood. From shore a woman's high, keening voice rose over the sound of surf, screaming to the village men, "Shark lines, who has shark lines?"

Those who had them responded, hauling the heavy, big-hooked lines from the village while the woman continued to scream. Now she was calling for chickens, and other women and men of the village collected the fowl, killing them or not, running them to the shore. The men with the shark lines impaled whole chickens on their hooks and hurled them to the inlet, where the sharks still swam in quick excitement, dorsals slicing the water inside the breakers and beyond.

A mother's greatest agony must be witnessing the death of her child. This woman--Martinez's mother, Chilo's grandmother-endured just that. With rage overtaking shock and pain, she ordered the fishermen again. "Let them eat; don't set the hooks," she pleaded. "Let them swallow, let them eat..."

A few of the chickens cast into the water fell from the hooks and the sharks snapped at them, their excited feeding now becoming a frenzy. In moments they discovered the baits still fast to the hooks and took them. Groups of men held each line as though queuing for some macabre tug of war. As each shark was hooked, the men began a slow march away from the water, young Chilo among them, pulling the thrashing and twisting sharks toward shore.

SWEPT AWAY

Ironically, cross currents had carried the two men who clung to the dugout's remains through the surf and south along the beach. They were miraculously unharmed. Some of the villagers ran to help them, pulling them through the undertow to safety. At the inlet the hooked sharks were dragged through the wet sand, heavy bodies arching, jaws snapping like living traps seeking anything on which to close. The fishermen clubbed and shot them. Seven sharks were taken; when they were opened, most of the remains of Chilo's father were recovered.

A pyre was built from the driftwood, the people of the village gathering near as the man was cremated on the beach. The old salt-impregnated wood burned sometimes blue, flames fanning high in the wind. Chilo's mother died one month later.

More than 30 years have passed since that terrible day. You wonder what stays inside a person who has lived through such horror. Today Chilo is a quiet man of hard pragmatism and reserved watchfulness. Only during the chase--times when his boat crests a swell and rolling tarpon are sighted, or when he steps into the living kaleidoscope of the rain forest to hunt--can you see excitement in his expression.

Though Martinez waged no obvious vendetta after his father's horrible death, I would not want to be a shark that encroached upon anything he was doing. I last saw him, quiet as always, taking a skiff from the lodge across the river to the village. Across the flat, moonlit water, the wake scribed a sickle shape--a giant question mark, the man and boat winking out of sight like the dot at the base of that punctuation. Downriver something large and unseen broke the surface, only once. Even the jungle was still.

The Deadly Sea Creatures of Costa Rica

BARRACUDA Hooked barracudas sometimes explode in a surprise launch boatside. Holding one by its gill cover is okay unless your hand slips--a sure back entry into the fish's tooth-studded mouth.

PORTUGUESE MAN-O-WAR This jellyfish produces painful, occasionally fatal stings with its 100-foot tentacles. Swimmers are most at risk, especially on Costa Rica's Pacific coast, but stinger-decorated fishing lines pack a wallop.

HAMMERHEAD SHARK Scary-looking and as numerous as the bull shark, this maneater patrols river mouths and surf lines as well as offshore. It will take any fish you hook unless you fight it fast.

TARPON A target game-fish species of Costa Rica's Caribbean coast, the high-leaping silver king can jump in your boat, smashing your tackle and your bones. But you didn't come all this way for bream fishing.

CROCODILE American crocodiles dwell in brackish water. Growing more than 20 feet long, they love pigs, dogs and monkeys. A good way to meet one is to dangle a dead fish up a jungle stream.

ICAST and IFTD 2013: What Are You Most Interested in Hearing About?

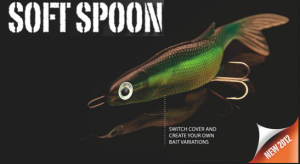

Fishing Articles : Soft Spoon- spoon and swimbait Combo

Pursue Leisure and Recreation With Outdoor Adventure Camps

Copyright © www.mycheapnfljerseys.com Outdoor sports All Rights Reserved